No Instructions in My Music: Brendan Fitzgerald Interviews Will Redman

Transcribed by Ethan Hayden

In preparation for the release of Wooden Cities‘ album, PLAY, the ensemble’s director led a conversation with Will Redman, composer of Book, the composition that is the centerpiece of the band’s album. Audio of that conversation, and a transcription, follow below…

What you just heard was part of a piece called Book written by Will Redman in 2006. My name is Brendan Fitzgerald from the music group Wooden Cities, and you can hear that recording and more on our album called PLAY on Infrasonic Press. I sat down with Will to talk about his music and experiences around Book.

Will is a composer, teacher, and percussionist living in the Baltimore area. He’s involved with an avant rock group, Micro Kingdom; his percussion quartet, Umbilicus; and the chamber music group called The Compositions. He teaches at Towson University, and we joined him for a call as he sat on a half-pipe he’s building in his dining room.

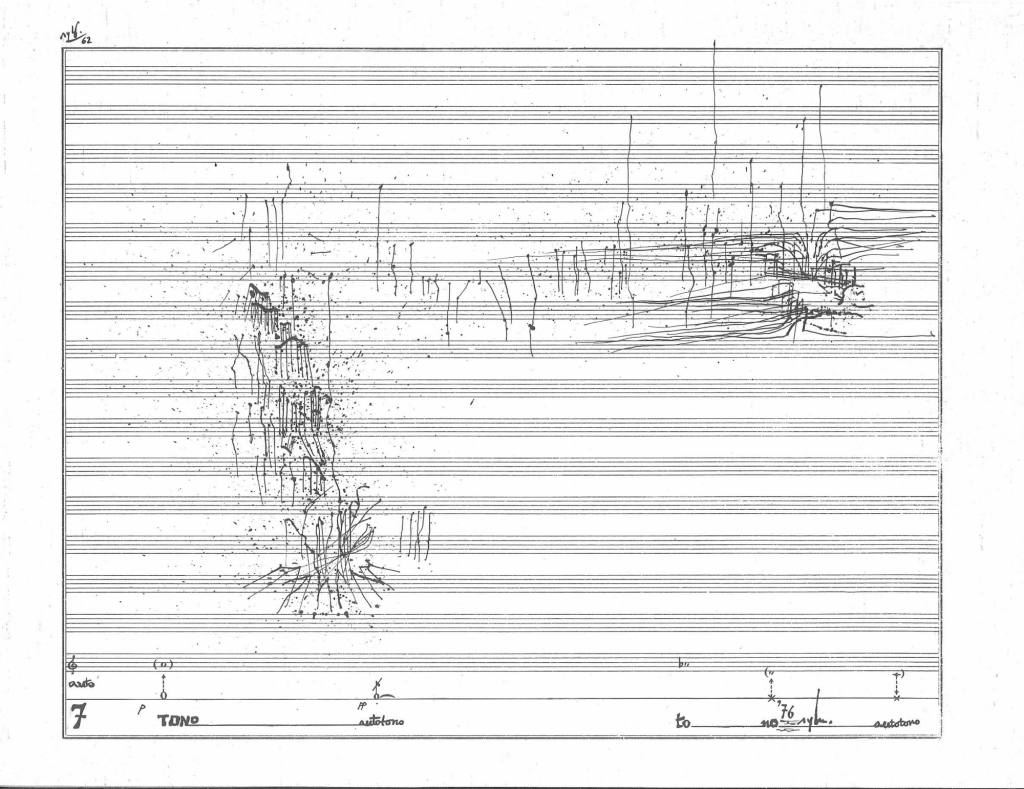

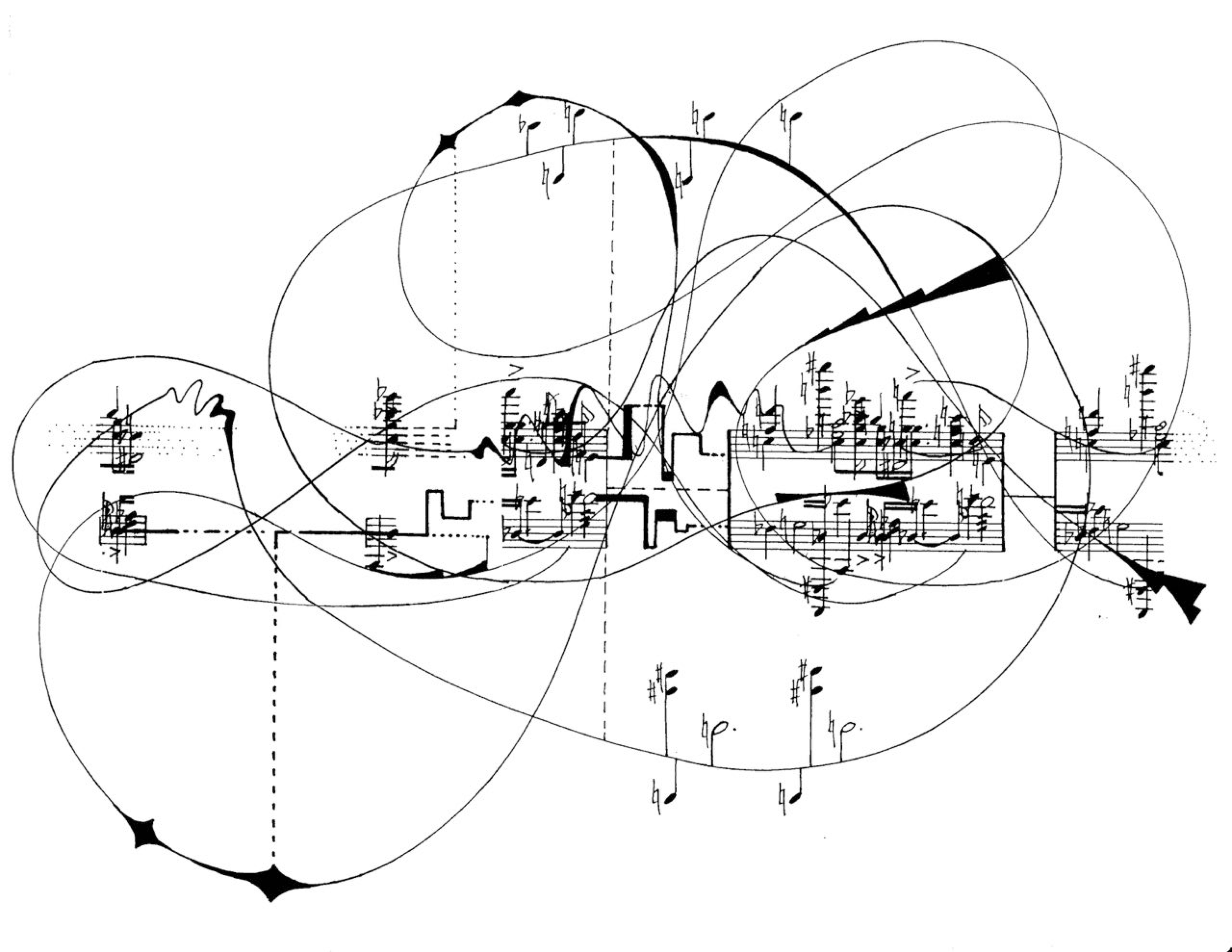

Will talks about his music in an important context of community and the people who make art together, and the intent behind developing what most would call graphic notation—but what he rightly calls unsystematic notation. He shares stories of several “aha” moments in developing this notation, and how performers have taken his representations of sound far beyond what he could have imagined.

We had a wonderful time catching up with Will, and I hope you enjoy our conversation.

Brendan Fitzgerald (BF): You know, we’ve been playing Book for a good number of years, and we’ve kind of had some correspondences back and forth. It’s sort of lived in its own space for [Wooden Cities] for so long. I was hoping today we could kind of dig a little bit into where the piece came from, your interest in graphic notation, and how that has changed with the piece.

For the uninitiated, do you mind just describing a little bit about your approach and graphic notation in general?

Will Redman (WR): Oh, my approach?

BF: Yeah—we don’t need a whole seminar, haha.

WR: Yeah, that’s a dangerous rabbit hole. Don’t talk to me at a party, unless you want a lecture.

So for me, I guess it starts when I was a young lad. I came to music pretty late, as an 18-year old going to college. The time that I was really getting interested in reading notated music, and realized I could also write that, and that it didn’t always have to look a certain way—that all came at once.

I guess one of the first two pieces I ever wrote was some sort of invented notation. My first composition teacher was Stuart Saunders Smith, and he did some really nice graphic scores. But then I found stuff in music books: Sylvano Bussotti, George Crumb, and [Brian] Ferneyhough and the whole New Complexity thing. And I was like, “Oh my gosh, this guy drew this with a pen, and and it’s wild and looks like fun!” So I got really into that, and then it got to a point where I was writing this music that was really specifically notated, and it was really hard [to play]. And I’m not an outgoing person or anything—I couldn’t get anybody to play my music.

I also improvised a lot and the people I was really close with were improvisers. The improvisors didn’t really want to engage with the music I was writing, and I didn’t really know the people who would have had that skill set.

There’s all these composers, Anthony Braxton—I should mention that name, he’s a hero of mine. I saw a concert of some of his students one time back in the ’90s, and they did this thing where… I guess the music was notated, but I couldn’t really tell—it was somewhere that wasn’t improvisation and wasn’t notation. I had this moment standing knee-deep in the ocean one day: I had to make this music that somehow my improvising friends could play, but that made me feel like a New Complexity composer when I was at my desk writing.

BF: Wow, yeah! When I look at it, yeah—you did it! I’ll say that.

When you talk about, the idea of, “I want people to play my music,” and increasing accessibility with this idea of not having to restrict or make it over-complex in order to achieve an effect. But what stands out to me is this interest in this DIY kind of thing, where you’re like, “I just need people to play my music.” And, I think that’s something to note along that journey, too, right?

WR: Yeah, it was a very practical decision in that sense. There are certain specific people I wrote for: a friend of mine, John Dierker is a reeds player (tenor saxophone, bass clarinet, etc.), and I was always trying to write music for him and I’d ask him how he did certain things. And he’s like, “I don’t know, man, I just blow and this sound happens.” So I thought, if I put something in front of him that looked like it maybe had some note or rhythm or something that looked kind of like music, but I was like, “You do your thing,” then he would play something I would never even be able to think of.

“There’s no instructions in my music, which unnerves people sometimes.”

That music of mine that’s like that, I wanted it to be something that you could actually sit down… You know, in Book, every quarter inch is an eighth note. It’s metronomically spaced, you could put a metronome on a play a lot of that in time. And I have, and other people have. But then you could also walk on stage and I could hand you a page and just be like, “Let’s play this.” Or you could never have played an instrument before. Or you could not even play an instrument and do some other activity, like just… look at it and go, “That’s neat.”

BF: Yeah, it is. For anyone who hasn’t seen the score for Book, the piece is, honestly, visually beautiful to see. In the same way that Crumb is, or the New Complexity things with all these big beams, twists and turns, and all this beautiful stuff. But I think you’re also describing democratizing music-making, taking away barriers. Just because one is not the most technically proficient doesn’t mean that they can’t make this music as good as the most technically proficient, right?

WR: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, a big part of my background is punk rock, skateboarding, DIY car repair, and things like that—a very working class background. I’m like, “Hey, I’m a guy who’s just trying to figure this music thing out, and anybody who wants to figure it out can be part of it.” Maybe there’s a period at a certain point of, being a snotty younger person and being a little snobby about music and new music and all that. But I think that was short-lived for me, hopefully, and opened up very quickly into, “This music stuff is for everybody and I just want to see people do it and to be there for it.” The accessibility thing, to be able to be able to access it and just do what you want with it—there’s no instructions in my music, which unnerves people sometimes. But, I’m just handing you these musical drawings, and you get to go do whatever you want with them and report back (or not). Maybe I won’t even hear it. You know?

This transcript will continue to be updated in the coming days, check back for the complete interview or listen to the audio recording.