By Adam Drury

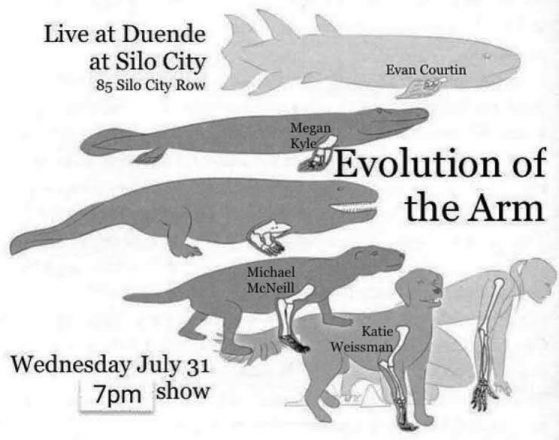

with Evan Courtin, Megan Kyle, Michael McNeill, and Katie Weissman

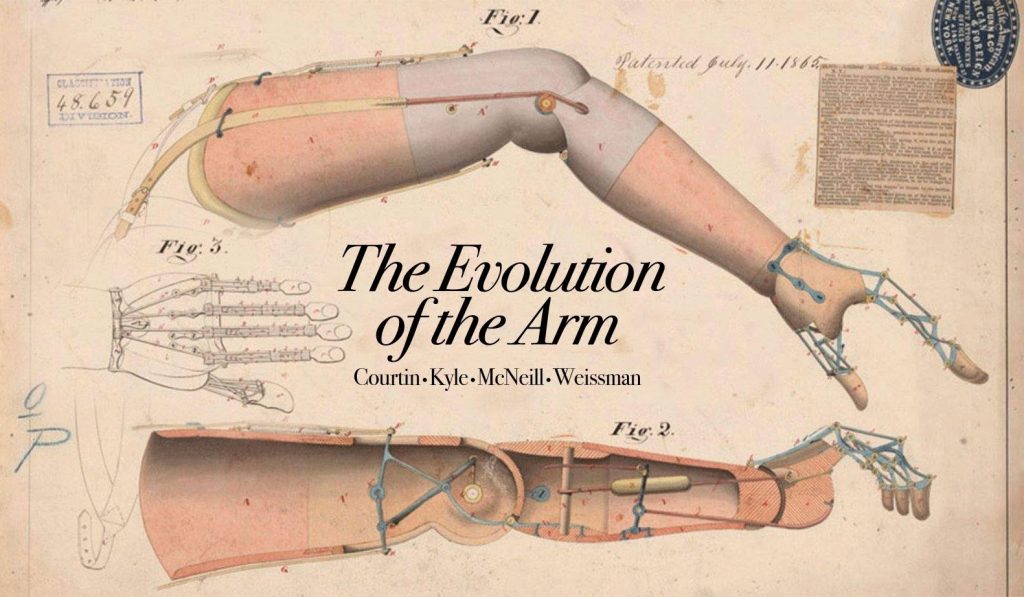

The Evolution of the Arm (EotA) are fearless musical cosmonauts for whom nothing is out of bounds and nothing too wild to try. Drenched in classical and jazz tradition, yet interested in moving beyond those toward a new musical expression, members of EotA cite everyone from Beyoncé and 100gecs to composers Mauricio Kagel and Pauline Oliveros and painters Agnes Martin and Howardena Pindell as influences and inspiration for their collective aspiration to listen to each other and make music with clear structures that maximize intention, imagination and artistic freedom.

My conversation with EotA about their upcoming album Sounds Like was wide-ranging, sweeping through the band’s departure from tradition, their exploration of technique, trust and telepathy, and their travels through the astral plane.

AD: Let me ask you about the evocative title to your band, The Evolution of the Arm. You probably know that we no longer view evolution as an optimizing, competitive process, a “survival of the fittest.” Instead, we’ve come to understand that evolution is a haphazard and contingency-laden collision of cooperation, mishap, and dysfunction that has more to do with the leftover, the unused, and the discarded of nature’s ideas than any movement toward perfection or balance. Do you think your project comments on this evolved view of evolution in any way?

MM: It does now!

EC: That’s an angle none of us have considered…

MK: But it does make sense to me, though. The kind of normative, classical framework is: always be the best version of the specific, limited tradition. We pretend that what’s “good” is a kind of universal, and you’re just supposed to become a better musician. But better actually means just better in a specific tradition; classical music isn’t the pinnacle of civilization or music, so we’re trying to dismantle the hierarchy.

KW: What I like about improvising is it’s all the “mistakes” or what I couldn’t have planned that I end up loving the most. Even in our last improv session I was playing these random out of tune intervals, and I hit on a close-not-quite-unison sound, and I couldn’t have gotten that intentionally. Here, we’re free to explore the mistakes.

MK: The band isn’t really interested in the “classical standard;” we don’t want to be there. We’ve all learned to play and draw from that technique, but what comes out is our sense of trying to be something else.

MM: Another tradition we’re steeped in is jazz, which comes through in some of the ways we approach improvising. That does a lot for how the group sounds. But our improvising is also informed by traditions beyond so-called “jazz” — improvisation has been a major part of classical music since it’s been called that (or something we might call that). For me, and I think for each of us, it’s about putting ourselves in a context or situation we’re not immediately comfortable with, so we can’t play the same old stuff. It’s about setting yourself up to find new things you can do, and doing things you wouldn’t try to think of right away.

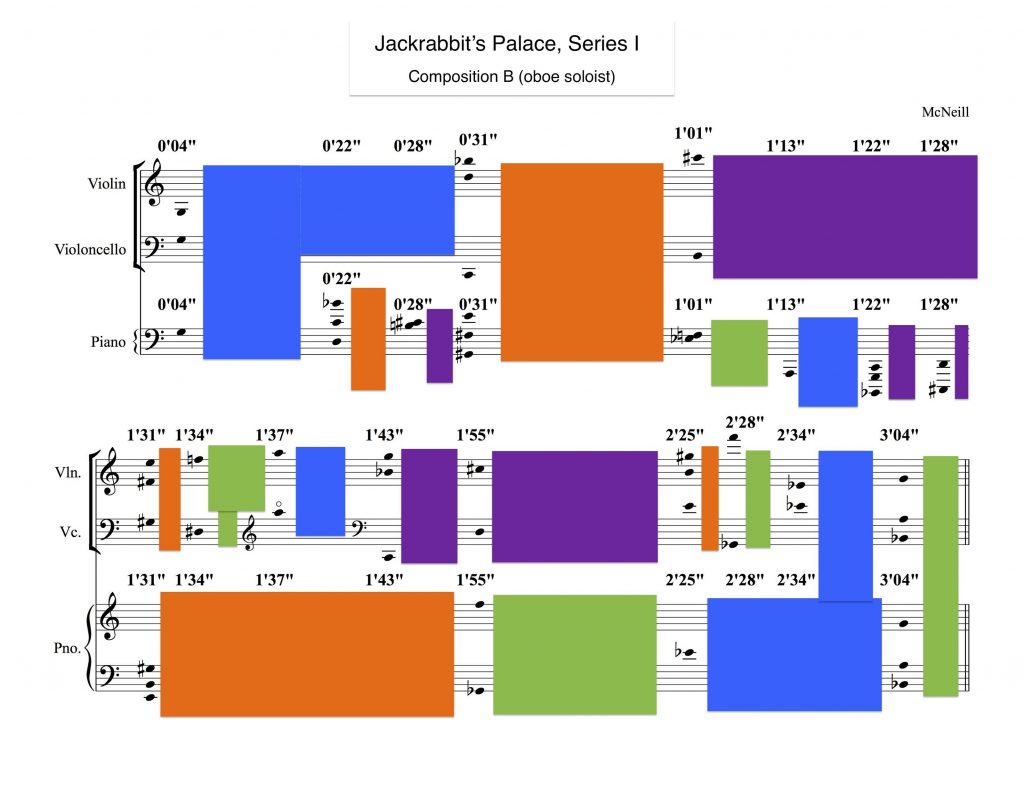

MK: The parameters of the compositions, like the Jackrabbit’s Palace Series, forces you to—

EC: —get out of the comfort zone. It’s controlled chaos.

KW: We’re trying to take our training and influences and transcend all those components that came into it, to take everything we know and have learned and figure out how to put it back together collectively as something else.

Evan brings up the topic of the band’s process of “telepathic improvisation,” a pandemic-prompted practice of playing together, only apart, in their own spaces, and unable to hear what anyone else is doing.

EC: Take the telepathic improvisation we’ve been doing as an example. Improvisation isn’t what we play or hear in the moment from our peers, like it typically is. Ideally, we’re connecting in the astral plane, feeding off each other in that dimension. And we can do that because we’re well-versed in each other; we know how to play together.

AD: Do each of you unlock ideas in the other?

EC: I would say so. We each have moments where even though we’re all in separate physical spaces, we’re waiting for each other, providing space for fellow musicians to take the limelight for a moment. It’s bizarrely cohesive in a way we can’t explain yet.

AD: I want to hear more about this process, and maybe you could reflect it through the unconventional metaphysics your band is crafting to describe its instrumentation and approach to composition. Here are some terms taken from the copy about EotA: “interdimensional,” “unconscious telepathy,” “parallel universes,” “fractured identities”. What is it about your music that demands this metaphysical language?

EC: Around the time we started coming up with words to describe our band, having that concept of the telepathic improvisation on the astral plane fresh in our heads really informed a lot of those choices.

MK: It felt like the logical place for us to go. It wasn’t a leap, it felt like something we had already been doing, so that’s why those words felt right for the group.

EC: I definitely agree with that. Those words can be applied to all of Mike’s compositions, which feature as much notated music as they do improvisation.

KW: With “Pawns” especially, Megan and I have to be super-connected. We perform it with Evan in front of us and he can’t see either of us at all. The idea is that we have to know and trust each other to the point where we can anticipate what the other is going to do, and the telepathic music has brought that out starkly. But even playing together, to execute the music, I have to know: how long after I see Megan move do I actually hear the sound? How does her reed work? And she has to know how my bow works. It’s a technical, physical way of knowing each other, of knowing how Megan relates to her oboe and how that relates to me.

MK: I also think of interdimensionality in terms of genre. Finding wormholes through stuff and pulling stuff together that’s not typically connected. It’s also about the relationship we want to create between notation and improvisation. Notation and improv both involve choice; our music has so much space for the performer. That inter–, that in-between space, where the instructions are: be free, but only here; play this note, but only once and then in a few seconds you can be freer. We’re creating different dimensions or levels of the score, lifting it off the page.

The band played me an assembled video recording of a telepathic improvisation session from April 25. Watching it, I notice immediately how focused everyone is, yet they all appear to be staring off into another realm.

EC: We think we all agree that’s the best one we’ve done so far.

KW: There’s no score. You have to be videotaping and recording yourself. We each start meditating five minutes before playtime and then at 30 seconds to playtime you have to clap. Then you play for five minutes and then you’re done.

MM: A few times we’ve had maybe a couple of words of an idea. “Stabby” was one. But not this time.

MK: For that one [“Stabby”] we tried to line up on really short notes.

KW: We didn’t line up.

MK: But the result was still interesting…

The band disagrees somewhat about this.

AD: Okay, so what makes the difference between a good result and a bad result?

EC: It sounds like it was composed and that we had a game plan. It’s the ultimate “jokes on you” kind of thing. The more we’ve done these, the more we come to realize that these are quality recordings that we’re making and that they’re coherent and cohesive and can stand on their own as works of art. That’s mostly why we’ve continued to do them.

MK: They all have some kind of arch to them. They’re interesting to listen to. The ones I didn’t like had low energy; or they just weren’t interesting as a listener.

KW: For me, it’s: OMG is my entire life a joke? I can do this telepathically, but if you put us in a room it would sound exactly the same. So what’s real then?

EC: Yeah, so what’s the point of anything?

KW: It’s a pandemic-adjacent feeling, too…

MK: A foundational rule of improvisation is that you should listen, be listening. But the fact that we’re clearly not able to listen in a physical sense, but we can still make something that sounds as coherent as if we were in the same room…it makes me wonder, was I ever really listening at all? Am I a terrible musician?

KW: Or am I actually telepathic?

MM: Or is it just an attitude of listening? Is it the fact that we’re in an attitude of listening more than that we can actually hear?

MK: We had to learn how to stay in an ensemble mindset, leaving space for other people, having that group attitude, knowing the style and our styles, despite being an individual alone in the house. We had to learn that at the beginning.

AD: You’re dealing with temporal dislocation.

MM: Telepathy is instantaneous, it has no latency! Online recording has latency. This feels creatively fulfilling in a way that over Zoom, wouldn’t feel as good. Something is happening but you don’t know what happened until later.

KW: It’s a weird space between the known and the unknown.

EC: And as an improviser you don’t know what you can do until you do it. And you’ll never replicate it or create the same effect again.

KW: Once you do it, you would have to practice for thousands of hours to do the thing that you just did unconsciously. Once you do it, you can’t do it again.

AD: This quest for a new music, new sounds and techniques, a new process: does all this speak to a kind of unmet desire, a sort of unslaked musical thirst that, for example, motivated the departure from the classical chamber format and the interest in writing and performing only your own compositions?

MM: As far as convening this band for our first gig, at some point I said, who are the people I never get to play with, and these three were at the top of the list. I had some existing music and some other stuff I wanted to write for instruments that have enough similarities and contrasts that it sounds pretty complete. In terms of the music, I guess it’s about different approaches to rhythm and harmony, to be very concrete about it.

MK: I feel like this group is a very interesting and fulfilling laboratory to try stuff out. Early on we decided to play only our own music. We all met in Wooden Cities, a larger composer/performer collective; but for this quartet, this little unit was doing its own thing. We have plenty of experience playing other people’s music. It felt good to set this boundary and say, here’s our little playpen. Earlier this spring I had an idea for a telepathic piece that we were able to try a bunch of times. It didn’t always work; I’m not satisfied with it yet. The band’s spirit of generosity means this is a place I can bring it and workshop it.

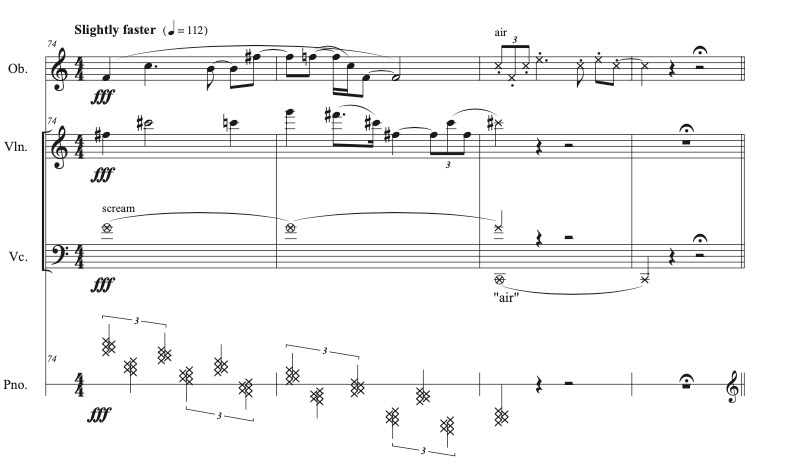

EC: We’re versed enough on our instruments and areas of expertise, that if one of us came to the other and said, I don’t know what the outcome is going to be—doesn’t matter who it is, we’re always game to play it. Sometimes I’m asking Megan to do weird things with her oboe.

Megan tells a story of Evan’s video request for Megan to play a note on her oboe and while slowly pulling the reed out of her mouth, transition into a scream at the same pitch.

MK: My niece found that video on my phone and she couldn’t stop laughing!

EC: We’re still trying to figure out what the context is for that. The point is that there’s no idea that’s too out there that you can’t bring it to others in this quest for a new technique, a new sound or a new device. What more can you ask for?

KW: I feel like making the decision to only play our stuff is what made this group different from everything else I do with these same people. The pieces are more liberating because they assist in forcing you to be more creative, because you can’t just do whatever you want, which might always be the same thing. For me that was the compelling thing, to push me to continue to get better. It’s also a rewarding experience to work with the composer and have that give and take. You create the music together.

MM: The fact that we have had somehow not that many performances (due to pandemic business and distance), there’s a lot of room to experiment and not a lot of pressure. There were some very exciting days where we had to learn all this difficult music very quickly with almost-but-not-quite enough rehearsal and just get it done. And there’s experimentation that happens there by necessity. We’ve really been fortunate to be able to take the time to work on all of these things, and have never been in a situation where we had to put anything out in concert that was rushed. We’ve done a lot without a lot of pressure.

AD: Speaking of performances, do you hope EotA and Sounds Like will appeal to fans of classical and chamber-esque instrumentation? Or are you on the hunt for a new listenership?

EC: It’s an interesting question, because I feel like in Buffalo, NY specifically, our listenership is finite. There are only so many people here that would be interested in the sounds we would have to play—and I think this is larger than that. I think this kind of music tends to suffer from the stereotype that you have to be of a certain intelligence to know it and listen to it and experience it and enjoy it. For me, that’s not how I respond to it at all, but it’s impossible to change people’s beliefs on this kind of music. The quest for sound and technique is motivated by my desire to break down those barriers and make this music more accessible, with the inclusion of just the absurdity of a potential idea. Going back to the oboe scream, the idea is to make listeners laugh, put them at ease, help them realize it’s not as cerebral as they think it is—it really is just someone trying to make you laugh. The protocol of it all… it’s really over the top, and so antiquated: why do we have to do this? What I like to think I strive for in my compositions is to put at ease those ideas of uber-seriousness and highlight the absurdity of it all.

Michael alludes to Sounds Like’s Lynchian overtones and Twin Peaks references.

MM: Seems like a very Twin Peaks thing, the moment of levity in something serious. In that first episode of the first season, it’s so grim and then there’s all this stuff that’s super hilarious. It’s like, is it okay that I’m laughing here?

EC: I’m fantasizing about a piece meant specifically to be performed live on Twitch. There’s a theatrical element I’m trying to work out; different scenes have their own soundtrack. The big joy of having people like this to play with is their fearlessness, in that you can try these new things and not worry about what the perception is. If this is the stuff we do in our music, our listenership will grow to understand: that this is The Evolution of the Arm and this is what they sound like!

KW: We might scream bloody murder on stage, so you’d better be prepared.

MM: Katie specifically is the screamer.

EC: “City Juice” isn’t on the record but there’s a good healthy scream in the middle of it.

KW: But that’s back to experimentation again, the experimentation of getting asked to scream onstage exactly how you want me to do it: for the correct duration, at the correct volume, and really work on screaming precisely.

AD: Evan mentioned the title of the record, Sounds Like. To me it seems like it has a playful ambiguity between the self-referential and the allusion to your classical and jazz precedents. What do you like about that title?

MK: We don’t know.

EC: The working title was We Sound Like This (that’s a Twin Peaks reference).

MK: For me, it was the dual meaning: the Evolution of the Arm sounds “like this,” but also here’s a collection of sounds that are “like this.”

AD: Walk me through a particularly striking instance of your unique process. I’m especially interested to hear about the relationship you forge between composed notation and improvisation. Let’s take “Starting Positions” as an example, the opening track. Where do you start? Are there false starts? How do you know when a piece is done evolving? Is it ever?

MM: I had some vague ideas in my head. I wrote it as I was driving up to rehearse and play for our first gig. Really it was just the bass line power chord riff, the unison melody, and everything else we just organically developed independently-together as we prepared to make it sound complete.

MK: Neither of my compositions are done, and I don’t know when they will be.

EC: Generally speaking, without a deadline, there has to be a point where you say, that’s it. You just have to let something go and move on.

KW: Doesn’t apply to me!

EC: I think, Katie, maybe in a way for you, it’s more like your interpretation of my music and Mike’s music is not a singular thing. You’re very thoughtful and detail-orientated, giving us options to work with. Definitely you could say, I could do it like this or like this. But you can do it like this…. The largely unspoken part of being in a group like this is even if you’re not a composer, you still have a very important say in how things are written.

AD: Do you have a favorite moment on the record? A favorite moment of composing and creating it?

MK: I have a lot of favorite moments. I remember enjoying all the glissandi on “Jackrabbit’s Palace 1C” that Evan and I do together, sliding from one pitch to the next soooo slowly. It makes your brain feel like it’s turning inside out. I love it! I have to do all kinds of weird technical stuff to make that happen.

MM: I said you could just start holding these notes from start to finish, or you could slide from one to the other. But they went to town! And it was amazing. A few times you’re going in opposite directions, and at other times it’s almost in unison.

KW: My large-scale favorite is the whole complete picture of the album, the whole journey from the beginning to “Double Memory.” The arch of the emotional journey is really satisfying to me.

MM: I think having “Pawns” in there, in a certain sense, relieves some of the density. Having Evan speaking the poem brings a very different mood, language and timbre. He really plays with the sound of those words in a very corporeal sense.

AD: I’m finding everything you’re saying about playing with and working through different technical approaches, what you call extended techniques, to be such an interesting way of creating and performing your own music. Tell me more about your approach to technique on Sounds Like. What are some highlights for you on the record with respect to your technical innovations?

MK: For me, it’s on “Jackrabbit’s Palace 1B,” where I’m playing the English horn solo. To get those sounds and tonalities, I’ve got the bocal pulled out about half an inch. This is a technique I first encountered in Tonia Ko’s solo oboe piece Highwire, and I especially love it on English horn.

MM: On “Jackrabbit 1B,” where Katie, Evan and I are playing the accompaniment, I wanted things we could all do that were similar to each other, so I suggested plucking the strings, as opposed to bowing them, since I can pluck the piano strings, too. There’s also the use of double-stop harmonics, which is something pianists didn’t really do until the twentieth century. But that’s not exactly “extended technique.”

The band debates the definition of extended technique.

KW: A lot of times it’s anything that is not “beautiful”—in the sense of the Western classical tradition’s desired sound—but strident, loud, harsh, or beyond the base level of what’s acceptable for timbre in terms of string instruments. For me it’s thinking about different levels and pressures; extended techniques are a gradient we employ all over Sounds Like.

KW: In the score for “Pawns,” there’s parts where Megan does slap tongue stuff. We’re both doing things that are more attack and noise than pitch, more like percussion. Col legno battuto—hitting the strings with the stick of the bow with a tapping/hammering motion, as opposed to drawing the stick or the hair on the strings—makes for some very cool and different textures, very rhythmic and percussive and not pitched.

MK: Slap tongue involves air sounds that are stopped abruptly with the tongue, but playing particular fingerings still changes the resonance of the empty tube to change the sound. It’s a cool effect when the oboe slap tongue and cello col legno come together, making a composite third sound that’s new.

KW: There’s a lot of string-specific timbral stuff going on in “Fluffernutter:” false/artificial harmonics; different bow placement stuff; touch fourth harmonics, Sul tasto…

EC: And in context we couldn’t have planned it better; couldn’t have done it without Katie.

AD: If Evolution of the Arm is also a revolution in new music, what possibilities do you hope the band opens up for listeners and musicians alike? What new imaginaries does your “Imaginary Chambercore” music make possible?

KW: I think a lot of times, I’m thinking about how our students who hear us will think about it. Maybe this is the first time they’re hearing a cello being played this way. Maybe it’s the first time that they’re seeing a concert that’s not in a concert hall, but in a bar. Those kids have been in a restaurant before, but have they ever been in a place where they’re exposed to music that might be so different from what they’ve heard before, being done by someone they know, who is also teaching them music? Imagine one of our friends comes and sees us play, and brings a friend: that could open up a whole new world of greater accessibility to even classical music in general, breaking down those barriers, like we talked about before.

MK: It gets back to not being so self-serious. Sometimes new music is treated like this intense, almost violent thing: “It’s Experimental and you have to take it Seriously!” I really like new music of all sorts, but I think what I like about what we’re doing, and what I do, is being more playful, playing around, listening to sounds for the sounds. And sometimes breaking out of the genre can be helpful, because you don’t have all this baggage you carry with you.

MM: Looking at it in terms of bringing this music to people, it’s not like we’re doing anything so absolutely brand new that other musicians need to pay attention and follow what we’re doing—that’s fun if they want to do that. But we don’t want to pretend like we’re the only people doing anything like this. But we interface with students, friends, family, random people who show up by accident, representing this world of music-making in the collaborative way that we do, with a certain openness toward sound and possibilities. For other musicians and audiences we hope this is another push, along with all the other examples we have, of opening your imagination to all kinds of different possibilities, and hopefully other people will come up with their own.

Sounds Like will be available exclusively on Bandcamp July 15, and streaming everywhere on July 29.