Wooden Cities’ WORK featured in Bandcamp Daily

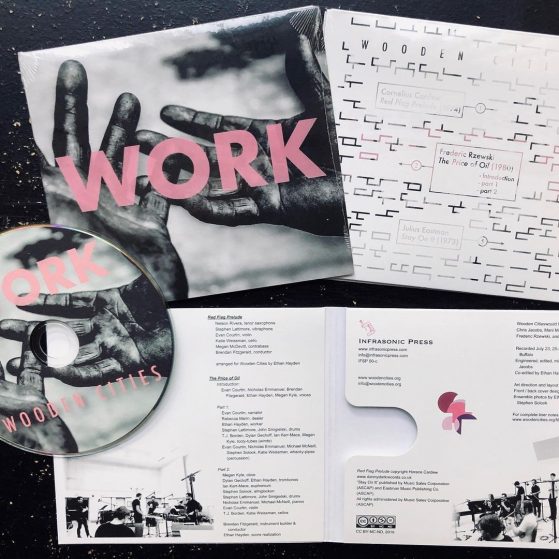

Wooden Cities‘ recording of The Price of Oil has been featured in Bandcamp Daily!

Writer George Grella profiles a number of recordings of works by the recently-deceased composer, Frederic Rzewski, saying of Wooden Cities’ recording:

“Rzewski never wrote an opera, though his catalogue includes two pieces described as “stage” works. He used text and spoken word so frequently, though, along with his fundamental sensibility for expressive—even narrative—music, that much of his work can be read as musical drama. The Price of Oil might be the nearest he came to straight drama, telling a narrative story through different characters. Written for two speakers and an open number of instruments, this piece tells the story of an oil rig disaster from 1980. Rzewski put together the libretto from newspaper stories and interviews with people involved. In this Harry Partch-esque performance from new music group Wooden Cities, one hears the hammering of mechanization driving home the real price of oil, which has less to do with dollars per barrel than the amount of money a company will pay to the family of a worker killed by drowning, explosion, or some other industrial means. Wooden Cities also recorded Julius Eastman’s wonderful Stay On It for this album, a perfect follow-up to Rzewski’s call to arms.”

Check out the rest of the article for profiles on more recordings.