Encounters on the Astral Plane: A discussion with The Evolution of the Arm

Transcribed by Ethan Hayden & Evan Courtin

with Megan Kyle, Michael McNeill, Evan Courtin, and Katie Weissman

The following Q & A session took place at the virtual release event for The Evolution of the Arm’s Telepathic Music Vol. 1. The event featured two virtual telepathic improvisations: one in which the band was improvising isolated from one another, which audience members could hear by switching between different Zoom breakout rooms. The other invited audience members to connect telepathically with one another. The evening ended with a question-and-answer session, which yielded an intriguing discussion about the band’s unique improv practice. With the release of the band’s second collection of interdimensional experimentation now released, we thought it was a great opportunity to share this discussion with anyone who missed the event.

Megan Kyle (oboe): I have one question just to kick things off. Mike, you were the one who pitched the idea of telepathic music to us. So how did you come up with it?

Michael McNeill (piano): Well, it’s actually an idea that came out of the 1970s or 80s. At the end of 2020, I was reading The New Yorker, and there was a little capsule appreciation of the experimental music venue in New York City called The Kitchen. And so they talked about some of the wilder things that had gone on in the early days of the venue. One of the things that they mentioned was a performance in which the audience was there at the venue, and the performers were somewhere else. I don’t even know if it was a music performance, or poetry, or dance, or film, or who knows what, but the performance was being delivered via telepathy. And that somehow stuck with me.

The Evolution of the Arm was getting together [online] on a fairly regular basis, and had recorded our studio album, Sounds Like, back in 2019.

We were wondering, “What else could we do to make music together?” Given that I live a few states away [in Virginia], and also, we were pretty well quarantined at that time—so even if we did live next door to each other, we probably shouldn’t be doing too much. So that’s where it came from, and we developed the procedure to synchronize and video record and so forth. And, we said, “You know, maybe it’ll be terrible,” but we ended up having a great time. And that’s why we’ve gone to all this length. So every couple of weeks, basically, for a year and a half, we’ve gotten together to do one of these and we’ve taken the trouble to touch up the sound (we haven’t edited or moved anything around, any of the audio production has just been to clarify what’s going on). And that’s the story of how we got here.

Audience member 1: When you all are gathering together to meet on the astral plane have you ever encountered anybody or anything else?

McNeill: Ooh, not consciously for me.

Katie Weissman (cello): I mean, I don’t know if I would know.

Kyle: I feel like we all come to it with whatever baggage we bring from our day and where we’re each at. My process when I’m meditating is to try to visually or spatially link myself with everybody in the ensemble. I think about where everyone is in relation to myself and kind of make this shape in my head of how we’re all arranged in space. Sometimes that process is a lot harder than other times—sometimes it feels like I’m trying to swim through maple syrup to get to everybody.

Weissman: I feel like sometimes I’m more called to interact with the sounds that are happening around me. But I also don’t really try to think too much and just play what I think I should play. So I’m not sure if I’m telepathically aware enough to know where the things I’m getting are coming from? Maybe we’re not actually connected directly to each other—maybe we’re connected to some central thing, you know?

Audience member 1: That makes sense. Thank you.

Audience member 2: Have you experimented with the length of time for the meditation you do before playing?

Kyle: Actually, no. We’ve stuck with three minutes.

Audience member 3: Why three minutes?

Weissman: Honestly, I definitely don’t usually do three minutes. I’m running around, and I’m like, “I gotta get everything set up, and my dog wants to go outside, and I gotta do this and that…”. So I’m lucky if I sit down in my chair and clap at the right time. So it’s already kind of a soft three, at least in my world. I think that three minutes is kind of arbitrary. Maybe we could think about doing longer and see if that makes a difference. We could do some experiments.

McNeill: Well, the one we did tonight was the first time that we had ever gotten together in the day before we played. So I don’t know if we’ll discover that that influenced it or not. I don’t know how we would know. But I previously wondered, “What if we just talked about our week for ten minutes, and then meditated, and then played? Would that do something different?” I don’t know. So tonight maybe we will find that that makes a difference.

Audience member 4: Does anyone have any favorite moments of synchronicity in your sessions?

Weissman: There was that one time recently where we were all doing the same pitch set stuff. I mean, that still just totally freaks me out! We’ll have moments where we’re all in the same register doing the same thing, or we’re all doing trills, or everybody else stops and one person will interject. I feel like there are always moments where I’m just continually amazed that this is actually happening and we’re not in the same room.

Kyle: We usually do the telepathic music, and then we have a band meeting like a half hour later. And then at the end of the band meeting we’ll play back what we just did—because Evan will have had time to mix it—and several times during that we’ll look at each other in the Zoom and be like, what?

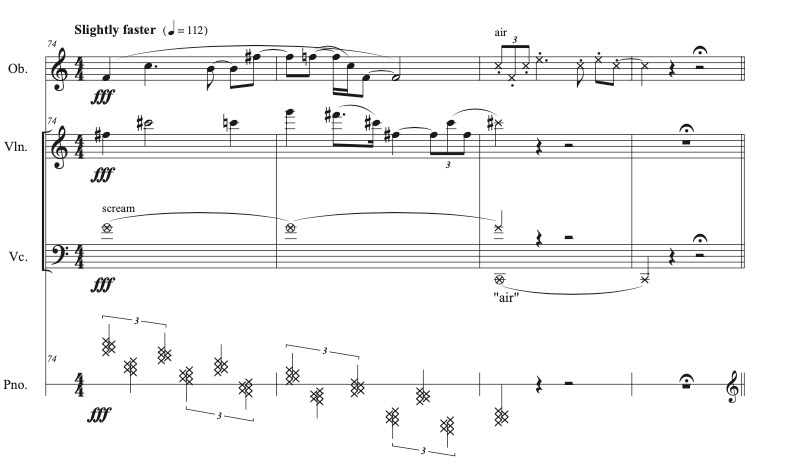

Like the one from May 5 [available on Telepathic Music Vol. 2], I really like. We’re all messing with edge-of-sound kind of stuff, and getting multiple tones out of our instruments, however that works for our instruments, and the fact that we’re all kind of doing this spectral sound all at the same time. First of all, I just like how it sounds, but it’s also just…weird. We did not talk about that, we did not plan that, it just, like…happened. That’s the one for me.

Audience member 1: How can you – how do you cue someone out because they can always join astrally?

Kyle: This is true.

Evan Courtin (violin): Forcefields.

Kyle: This is the maple syrup—sometimes someone’s trying to become maple syrup in my astral soup.

Weissman: I feel like we’re not exclusionary either. If somebody really wants to get in here, I mean, it’s not like we’re playing tonal pretty music anyway. Weird sounds are acceptable. So if someone’s coming in and trying to mess things up… I’m down. That’s cool.

Kyle: If someone can figure out what time we are doing a telepathic improv, and they want to do it from their house and send it to us… please do.

McNeill: Well, one idea that we’ve talked about, but haven’t yet pursued is to have a special guest. So that might happen at some point. Or we could even just post on social media sometime, “Hey, we’re about to do one if you want to jump in.”

Audience member 5: You know how humans have the tendency to see faces and stuff in nature, and find connections and stuff? What is it, Pareidolia? So maybe it’s just that we want to hear all the moments make so much sense and have so much meaning. Maybe we’re just all really into the process, because we really just love music and sound?

Weissman: That could be—we could be hacks! That was kind of like the first response we had when we did this the first time and listened to it. We’re like, “Wait a minute, does this mean that the rest of our lives are like… completely fake… and we actually don’t know anything about music?

Courtin: It was very existential.

Kyle: I definitely think that’s true, though. We do, we make stories out of whatever we hear.

Weissman: Megan, Evan, and I all play in Wooden Cities, and we did a gig in April that had a lot of improvisation on it. I found that being physically together again, improvising in the moment, I noticed that there were times when we just spontaneously played the same pitch. And I felt more connected to Evan and Megan than I did to all of the other people there. So I don’t know if that’s just because we’ve played together more than I’ve played with those other people, but it felt like maybe we did have something going on that was not just us happening to pick the same pitch material.

Courtin: Yeah, we’re all pretty well versed in each other’s style of playing. We’re just so experienced playing with each other that we don’t even have to be in the same room as each other now.

Kyle: I think it’s like all of these things just in a big lump all together. It’s definitely true that we can make meaning out of anything, but that’s not to say that discounts other cool things about it.

Audience member 6: If you guys are always improvising in five minute blocks, it might be interesting to try to take pieces from different sessions and put them on top of each other and see if you notice the same kinds of synchronicities. I’m not trying to disprove the theory or anything, but I think it’d be interesting to test whether it is our brain applying structure to it.

Courtin: You’re on to something!

Kyle: Yeah, I like it.

Courtin: We should try that. Everybody picks their favorite recording that they’ve ever made.

Weissman: Or just have the computer randomize it or something. Just put in the dates and have it pick for each of us.

Courtin: Yeah, then we would know for sure.

Audience member 7: Do any of y’all try to prank the others by playing totally different than normal?

Courtin: The closest that I can think would be days when any of us play something other than our primary instrument.

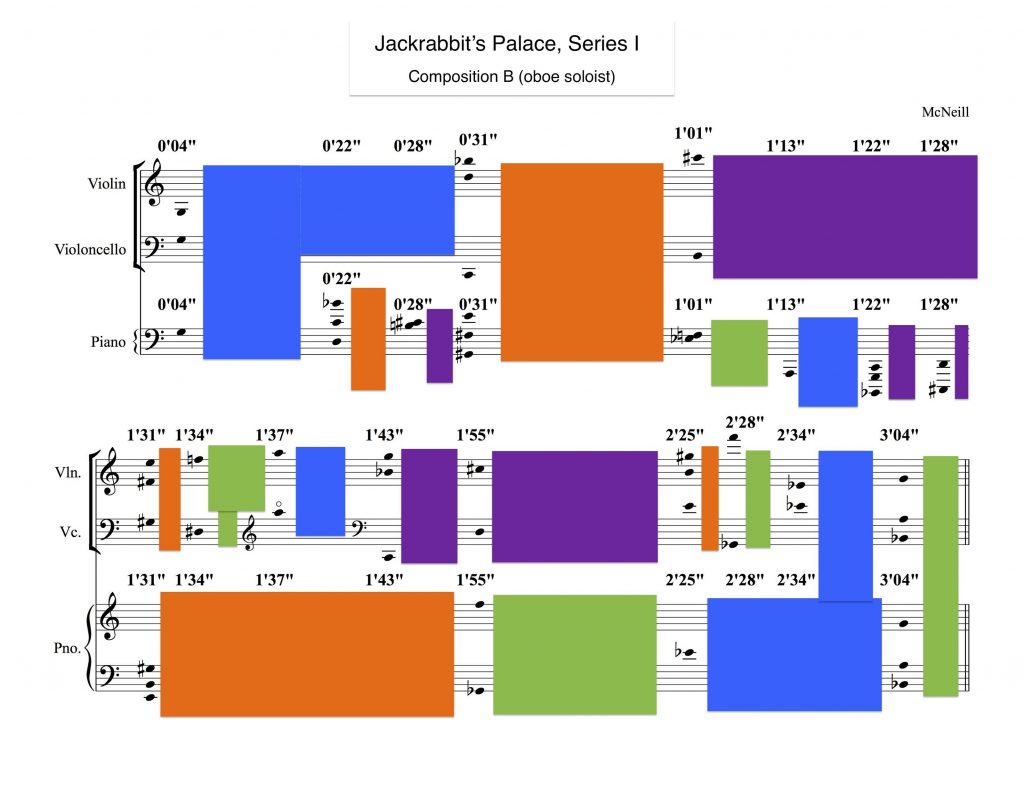

McNeill: Well, in the May 5 session, I was playing a granular synthesizer that I had never played in this context before. I have thought about actually trying to do something that wouldn’t work, just to see if it does work. My reasoning for doing the electronic thing that day was that I’d been doing some of that already and I wanted to try doing it in this context. I wasn’t trying to fool anybody. The short answer is the thought has crossed my mind. But I have not really tried to mess with anybody.

Courtin: I think the only time I ever tried to do that was when I got this crappy autoharp, and I had it sitting on my lap while we were recording, and then I would occasionally try to drag the screw of my bow across the strings. And it was so out of tune, and kind of weird…

Weissman: I think there have been a couple of times where we’ll play, and then when we’re texting afterwards I’ll be like, “Oh, I use my pedals that time,” and then Michael be like, “Oh, I was on the organ that time.” So I feel like we also sometimes sync up without knowing it by doing something different than we normally do. But that could just be because we’re like, “I’ve been doing this a long time, and I want to do something different.”

Courtin: Well, thanks everybody for coming!